Happy Friday, dudes.

🗓️ Today in History

May 9, 1962: America’s First Crash Landing on the Moon

Before Neil took that famous step or Houston had any problems, NASA sent Ranger 4 to the Moon and it smashed the landing. Literally. On this day, Ranger 4 became the first U.S. spacecraft to reach the Moon. The onboard computer failed, communications went dark, and it crash landed on the far side. But in classic American fashion, we still counted it as a win. It was a moment of Cold War one upmanship, showing that even when we fail, we fail loudly and on the Moon. This clumsy lunar belly flop paved the way for future missions each one a little less explosive.

❓ Trivia

What kind of animal was the first living creature launched into orbit?

☕️ Sponsored by Morning Brew

The easiest way to stay business-savvy

There’s a reason over 4 million professionals start their day with Morning Brew. It’s business news made simple—fast, engaging, and actually enjoyable to read.

From business and tech to finance and global affairs, Morning Brew covers the headlines shaping your work and your world. No jargon. No fluff. Just the need-to-know information, delivered with personality.

It takes less than 5 minutes to read, it’s completely free, and it might just become your favorite part of the morning. Sign up now and see why millions of professionals are hooked.

The Iditarod: A thousand miles, a bunch of dogs, and zero room for comfort

Every March, a handful of lunatics voluntarily sign up to sled across Alaska behind a pack of dogs. It’s called the Iditarod. It’s a thousand-mile race through some of the most miserable terrain on Earth. Think blizzards, -60° temps, frozen rivers, and a complete absence of anything resembling a bed or a cheeseburger.

The whole thing exists because, in 1925, a diphtheria outbreak hit Nome, Alaska—a remote town on the edge of nowhere. There was no medicine. No roads. And the nearest life-saving serum was nearly 700 miles away in Anchorage. Planes couldn’t fly because it was the middle of an Arctic winter and aviation in 1925 was basically just wishful thinking with wings.

So Alaska did what Alaska does: handed the job to a bunch of dogs.

A relay of over 20 mushers and 150 sled dogs passed the medicine like a frozen Olympic torch across the wilderness. The hardest, longest, most brutal stretch, through gale-force winds and whiteout conditions, was led by a dog named Togo, who ran more than 260 miles and saved the town. Togo was 12 years old at the time. That’s about the human equivalent of being 77.

But the last leg of the relay was handled by a different team, led by a dog named Balto. His team carried the serum into Nome, got the press, the fame, the statue in Central Park, the movie, the merch. Balto became the face of the operation. Togo got a pat on the head and had to wait 95 years for a Disney+ deal (shoutout to Willem Dafoe).

Classic.

In 1973, someone said “hey, let’s honor that near-death relay by turning it into a competitive race.” It’s basically the Super Bowl of sled dog racing, except instead of Beyoncé at halftime, there’s sleep deprivation and beef jerky.

Gunnar Kaasen with Balto

The Route

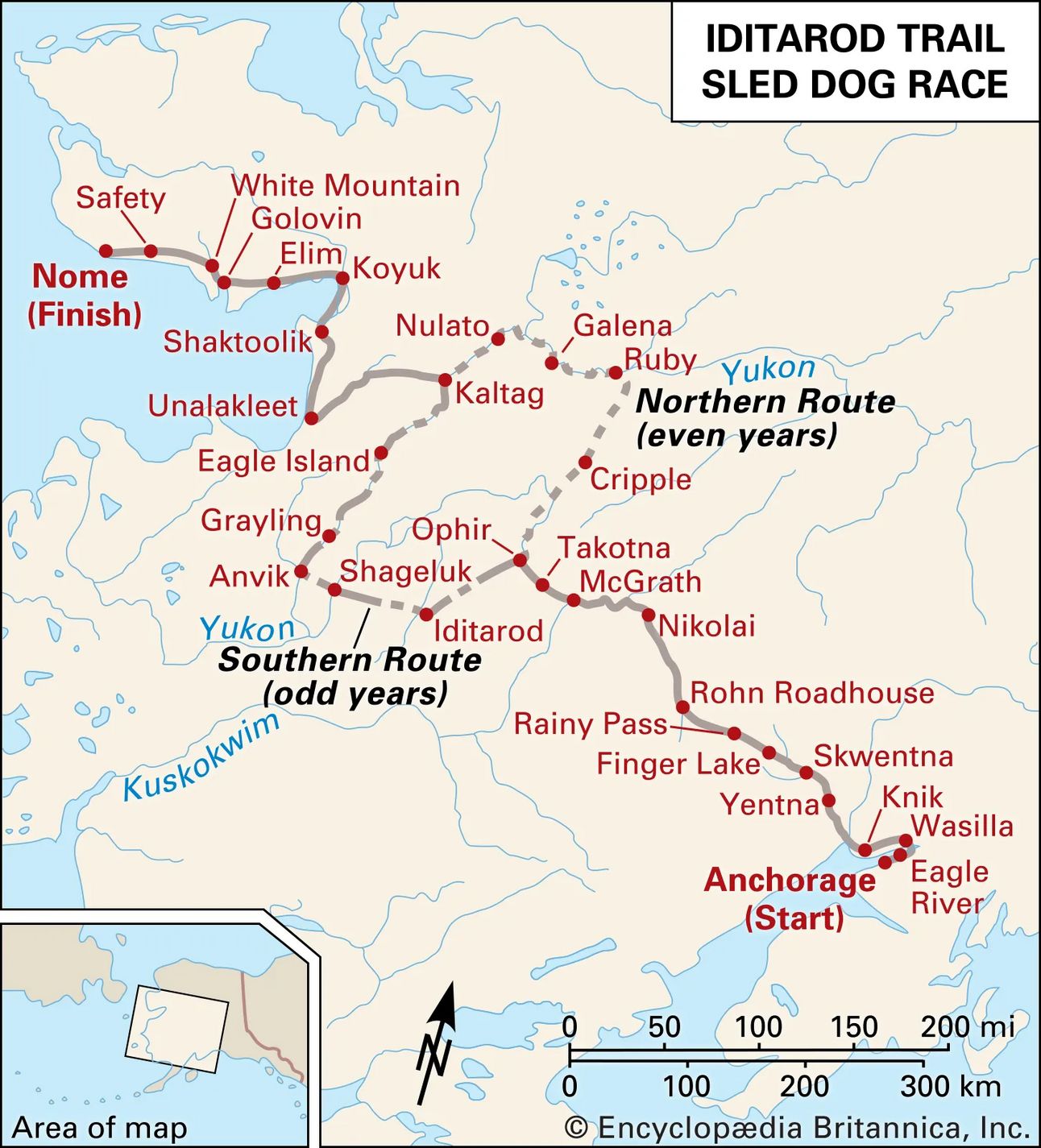

Depending on the year, the race covers anywhere from 975 to 998 miles.

The race kicks off in Anchorage with a ceremonial start, then restarts for real in Willow. From there, mushers and their dogs head northwest toward Nome, cutting through just about every type of miserable terrain Alaska has to offer. There’s a southern route used in odd-numbered years and a northern route in even ones.

The trail winds through the Alaska Range, across the Kuskokwim River, follows stretches of the Yukon, then hugs the Bering Sea coast until it rolls into Nome. That final coastline stretch is where you get some of the worst wind on the planet and just enough visibility to regret your life choices. There are 24 to 26 checkpoints along the route, offering mushers a place to rest, resupply, and have their dogs examined by veterinarians. Most are simple setups with small cabins or tents, basic food, and just enough shelter to recover before heading back into the cold.

Temps can drop to -60°F. That’s not a typo. That’s just interior Alaska in March being its usual cheerful self. The wind doesn’t help. Visibility can go to zero in seconds. There’s no cell signal. No hotels. No soft landings. Just snow, ice, and the occasional debate with yourself about whether this was a good idea.

The fastest racers finish in about eight days. Most take longer. There are no real breaks. Just a few hours of sleep on a bed of straw while your dogs snore and your body tries to remember what warmth used to feel like.

The Dogs

Each team starts with up to 14 Alaskan huskies. These aren’t your average fetch-the-ball pets. These dogs are built for pain. They eat 10,000 calories a day, wear booties to keep their paws from turning into popsicles, and somehow still love it. Vets check them at every stop. Mushers rub ointment on their paws like they’re tiny athletes… because they are.

Quick Facts

The last-place finisher gets a Red Lantern Award. It’s like a trophy, but more passive-aggressive

Most mushers sleep 2–3 hours a day.

First place gets about $50,000. Not exactly yacht money, but enough to restock your jerky supply

Dogs are the real stars. The humans are just passengers who know how to work a harness

Why It’s Cool

The Iditarod is a rare holdout from modern spectacle. No big sponsorships. No flashy production. Just a long-distance race through brutal terrain, where people and dogs deal with whatever nature throws at them.

🤝 In collaboration with Superhuman AI

Start learning AI in 2025

Keeping up with AI is hard – we get it!

That’s why over 1M professionals read Superhuman AI to stay ahead.

Get daily AI news, tools, and tutorials

Learn new AI skills you can use at work in 3 mins a day

Become 10X more productive

🥣 Stuff to Check Out

🎸 Song: William Onyeabor – Fantastic Man

📸 Photo of The Week

Secretariat winning the 1973 Belmont Stakes by 31 lengths

|

|

|

Thanks for reading. |